What Steps Did Californians Take to Apply for Statehood

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo – The 1850 Compromise

By the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ending the Mexican War, made public in Washington on July 4, 1848, the United States achieved its principal objectives: the acquisition of New Mexico and California and recognition of the Rio Grande as Texas' southern boundary. Along with the new territory, the nation also acquired an alien population and a basket of prickly problems.

There were even blunt spokesmen who went so far as to suggest that the United States had made a bad bargain in annexing New Mexico. Some years after the Civil War, General William T. Sherman, who heartily disliked the arid country and the people of the Southwest, was quoted as saying that "the United States ought to declare war on Mexico and make it take back New Mexico."

One result of such hostility was that New Mexicans for more than sixty years were repeatedly checkmated in their efforts to achieve statehood. This resulted in their land remaining a US territory until 1912, with officials appointed from Washington. Upon that vexation were piled others – problems with hostile Indians and outlaws, problems of education and economics, difficulties involving land and water rights and territorial boundaries. A central issue was the uphill job of adapting to a new pace and pattern of life, one ruled by a different philosophy. A country and people so unlike the rest of the United States seemed to have a poor chance of adjusting to the militant demands of American patriotism and economic nationalism.

Yet things were not as black as they appeared. The New Mexicans, like most pioneers, were accustomed to living by luck and hope, and they possessed some firm traits of character, often overlooked by American newcomers, that promised to see them through the hard times of their territorial days.

The Anglo-Americans entering New Mexico in the late 1840s and 1850s were small in numbers but large in influence. New merchants came, as establishment of regular stagecoach and freight service with the East stimulated business. The ranks of the military swelled with the construction of Fort Union (1851) and Fort Stanton (1855) on the Indian frontier.

The Anglo-Americans entering New Mexico in the late 1840s and 1850s were small in numbers but large in influence. New merchants came, as establishment of regular stagecoach and freight service with the East stimulated business. The ranks of the military swelled with the construction of Fort Union (1851) and Fort Stanton (1855) on the Indian frontier.

Besides the merchants and soldiers, there were the lawyers in frock coats and bat-wing collars. They descended in swarms, after the conquest, eager for political power and a slice of New Mexico's vast real estate, which represented the country's most visible wealth. The influential Padre Antonio Jose Martinez of Taos, a man of great intellectual gifts and social consciousness, likened the hastily contrived American government in New Mexico to a burro, adding ruefully "on this burro lawyers will ride, not priests."

The state of New Mexican politics in the period following the Mexican War was ready-made for lawyers and opportunists of all sorts to jockey for advantage. The assassination of Governor Charles Bent and the collapse in 1847 of the civil government created by Kearny left the area under virtual military rule. That situation continued over the next several years, while Congress debated New Mexico's future political status. In the meanwhile, persons on the Rio Grande broke into two opposing camps: the supporters of a territorial form of government, and the advocates of immediate statehood. In the main, Anglo-Americans, being in the minority, favored the territorial system. If New Mexico stayed a territory, its principal officials would be appointed in Washington. For that reason, the Hispanic majority tended to lean toward statehood; with the right to elect their own officials, they could easily put native New Mexicans into the highest offices.

Establishing Borders

The Compromise of 1850, among other things provided for the organization of New Mexico as a territory. The Compromise also resolved another complicated matter – an old Texas claim to that portion of New Mexico lying east of the Rio Grande. For ten million dollars' compensation provided by the United States government, Texas relinquished her claim, thus paving the way for establishment of a permanent boundary with New Mexico. The Territory, as organized in 1850, included the New Mexico and Arizona of later years, and a part of southern Colorado.

New Mexico's southern border with Mexico was less easily settled. In accordance with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, a joint boundary commission was organized and began (in July 1849) the task of surveying a dividing line between the two nations. The US surveyors working with the commission also had instructions to look for a practical railroad route to the Pacific, close to the boundary, and to ascertain the agricultural possibilities of the new country. In the course of the boundary work, it was discovered that the map used to establish the original treaty line had been inaccurate and that the border would in fact have to be placed thirty miles farther north. That slip meant withdrawing five or six thousand square miles from the United States and losing a potentially rich farming district in the Mesilla valley.

Before a serious dispute could develop, the American minister to Mexico, James Gadsden, negotiated in 1853 the treaty that bears his name, providing for the purchase of a large tract of desert land in southern New Mexico. The area offered an advantageous route for a transcontinental railway entirely on American soil, and its acquisition concluded the final adjustment of our border with Mexico.

The gold rush to the Rockies and the ensuing boom in population led to the formation of the Colorado Territory in 1861. As a result, New Mexico lost ground, for its northern boundary was pulled back to the parallel of 37 degrees. The reduction meant the territory was deprived of a valuable coal-mining area around Trinidad and of jurisdiction over those outermost settlements in the upper San Luis valley created by New Mexicans in the previous decade.

In these early years of adjusting to its new place in the Union, New Mexico absorbed a respectable quota of adventurers, gamblers, speculators, and renegade whiskey-peddlers from the eastern states – but it also got a share of those solid upright, intelligent citizens representing the glue that held a democratic society together and gave it its strength.

Of several newspapers that shortly began printing in the territory, one, the Weekly Gazette, called attention in 1856 to the newly formed Santa Fe Literary Club (whose president, interestingly, was a native New Mexican, Nicholas Quintana) dedicated to the expansion of knowledge and the holding of debates on burning questions of the day. Even more lustrous was the Historical Society of New Mexico, founded in 1859, probably the first such scholarly body to appear anywhere in the Far West.

Of several newspapers that shortly began printing in the territory, one, the Weekly Gazette, called attention in 1856 to the newly formed Santa Fe Literary Club (whose president, interestingly, was a native New Mexican, Nicholas Quintana) dedicated to the expansion of knowledge and the holding of debates on burning questions of the day. Even more lustrous was the Historical Society of New Mexico, founded in 1859, probably the first such scholarly body to appear anywhere in the Far West.

One of the guiding spirits behind the launching of the Historical Society was New Mexico's first resident bishop (later archbishop), Jean B. Lamy, a Frenchman by birth and a zealot when it came to charitable works and the mission of the Catholic Church. The new bishop, after his arrival in 1851, began a campaign to impose religious discipline upon the native clergy, whose lighthearted style of living caused him personal pain and scandalized the Americans. But Lamy did manage to begin a new era in the moral and spiritual life of New Mexico. Working with the energy of a whirlwind, he built in succeeding years forty-five new churches and a string of parochial schools.

Acknowledgments

New Mexico; An Interpretive History

Marc Simmons

New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1977

New Mexico; A Pageant of Three Peoples

Erna Fergusson

Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1955

Civil War (1861) – Indian Wars (1885)

Before education or the natural process of assimilation could make much headway, however, the people of the Southwest found themselves caught up in the momentous and ugly Civil War. It was an issue in which the New Mexicans felt only a small stake. The question of the expansion of slavery to the western territories, especially the New Mexico territory, dominated the debate in Congress during the 1850s.

Actually, in all the New Mexico territory, there were only twenty-one black slaves in 1861. Many politicians in Washington had long recognized New Mexico as a land unsuitable for slavery because the agriculture was small in scale and native labor was both plentiful and cheap. Territorial citizens had approved antislavery resolutions in 1848 and 1850. But a reversal in sentiment came in 1859, with adoption of a slavery code engineered by Miguel A. Otero, the New Mexican delegate to Congress. The code, designed to protect slave owners and their property, was more an expression of Otero's own Pro-Southern sympathies than it was a sign of any fundamental shift in attitude among territorial residents. Territorial New Mexicans desired to be left alone, for they saw little to be gained by joining in the political arguments between the North and the South over slavery and the legality of secession.

When the storm broke, splitting the country in half, New Mexico unexpectedly found herself part of the theater of conflict. From the outset, the newly formed Confederacy cast covetous eyes westward, where it dreamed of creating an empire that would reach the Pacific. Winning the West became a crucial aspect of winning the war for the Confederacy. The grand strategy developed by Southern leaders showed plainly that as a first step toward westward expansion, New Mexico must be brought into the Confederacy.

At the outbreak of the Civil War the affairs of the upper Rio Grande made it appear that Confederate annexation of New Mexico could be accomplished with relative ease. In the lower part of the territory there existed a hard core of Southern sympathizers – mainly ranchers out of Texas, who had settled in the Mesilla district. Most of the ranking officers serving in the New Mexico military defected to the South, bringing with them precious information on war material stored at several territorial forts. Added to those considerations, the territory's long eastern border with Texas and the vast distances separating her from the northern states would prevent help from arriving should New Mexicans try to avoid the inevitable take over.

The Rio Grande, for centuries the scene of fierce struggles between the Spanish and Native Americans now experienced the violence between Northerners and Southerners. Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley of the Confederate army and Colonel Edward R.S. Canby, commander of Federal forces in New Mexico first clashed at the Battle of Valverde. The Battle of Valverde involved the bloodiest kind of tough, stand-up fighting. At the end of the day Col. Canby's men retreated toward Fort Craig. The laurels, however, were anything but clearly won. Sibley's brigade held the fort and that, together with a lift in morale, was about all that had been gained.

One fly in the ointment of General Sibley's plan to conquer New Mexico territory was the fact that he had counted on winning over the Hispanic population, but he had failed to reckon with the New Mexicans' antipathy toward Texans, an outgrowth in part, of the Texas invasion of 1841, and more recent boundary disputes. General Sibley seriously miscalculated the strength of Union arms opposing him in the north.

The Civil War in the Southwest was indeed moving toward a climax. On March 27 and 28, 1862, regular troops from Fort Union, supported by the Colorado Volunteers, met the Rebels at

Glorieta, in what would become known as the Gettysburg of the West. Victory was snatched from the Rebels' hands when Major John M. Chivington of the volunteers delivered a wholly unexpected thunderbolt. The debacle at Glorieta and the retreat to Texas scuttled for all time Confederate hopes for an empire in western America.

One consequence of the Civil War in the Southwest was that the U.S. Congress finally turned its attention to the creating of another territory. Arizona was carved from the western half of New Mexico in 1863.

Another outcome was that it left the frontier open to attack by hostile Indians. It was not lost on the tribes seeking plunder or bearing old grudges that the white men were fighting among themselves, abandoning forts, and withdrawing troops for duty in the East. The ensuing bloodshed brought nightmare days to New Mexico.

Brigadier General James Carleton, a Californian, assumed command of the Military Department of New Mexico. His troops were ready for acting and he had fixed notions about how to deal with hostile tribes. "Wage merciless war against all hostile tribes, force them to their knees, and then confine them to reservations where they could be Christianized and instructed in agriculture."

The Mescalero Apaches of southern New Mexico were first to feel the effect of Carlton's strategy. Placing Militia Colonel Kit Carson in charge of troops in the field, the general sent his men to harry the tribe into submission. By March 1863, Carson brought four hundred warriors with their families to the new Bosque Redondo Reservation on the Pecos River in southeastern New Mexico. Here Fort Sumner, constructed by Carleton, stood guard.

The "Long Walk"

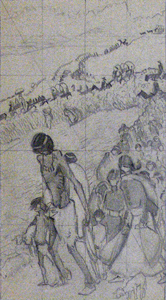

Next it was the turn of the Navajo, a people numbering at that time some ten thousand and inhabiting the crumpled and rock-strewn lands of western New Mexico. For years, Spanish and Mexican expeditions had tried to bring them to bay, but the Navajo proved too nimble, fading into the remote canyon lands whenever their enemies gave chase. During the last half of 1863, government troops marched and countermarched through Navajo land, destroying crops and orchards and capturing livestock. They fought no major battles, but their campaigning left the Navajo economy in ruins. In January of 1864, Kit Carson led his men into the depths of Can yon de Chelly, where, for the first time, he encountered a large body of Navajo. They were exhausted and starving, and at that point disposed to listen to a man who was known to be trustworthy. The tribe would have to emigrate to a government reservation at Bosque Redondo, Carson told them, but that was preferable to annihilation. Under the circumstances, the majority of the Navajo agreed, and they surrendered. That trip into exile, remembered in Navajo tribal history as the "Long Walk," had a parallel in the tragic Trail of Tears, when Indians in the southeastern United States during the 1830s were obliged to give up their homes and move west of the Mississippi.

yon de Chelly, where, for the first time, he encountered a large body of Navajo. They were exhausted and starving, and at that point disposed to listen to a man who was known to be trustworthy. The tribe would have to emigrate to a government reservation at Bosque Redondo, Carson told them, but that was preferable to annihilation. Under the circumstances, the majority of the Navajo agreed, and they surrendered. That trip into exile, remembered in Navajo tribal history as the "Long Walk," had a parallel in the tragic Trail of Tears, when Indians in the southeastern United States during the 1830s were obliged to give up their homes and move west of the Mississippi.

For General Carleton confining the Mescalero Apache and the Navajo people at the Bosque Redondo Reservation was the best way to keep the peace. But the reservation turned out to be an abject failure. The barren land in the Pecos valley could not support the nine thousand Indians crowded there, most of whom were not interested in farming, anyway. The drinking water turned out to be disagreeably rich in alkali, having a stronger effect on the stomach than castor oil, as one soldier stationed at Fort Sumner wrote his wife. The federal government failed to provide adequate supplies to support the Indians during the period that they were getting established. And putting the Mescalero and Navajo – traditional enemies- together on the same reservation was soon recognized as a colossal blunder.

With an end of hostilities and the virtual extermination of the buffalo, which quickly followed, the vast grasslands of eastern New Mexico were suddenly thrown open for settlement. Only some stray Apache bands in southwestern New Mexico had to be dealt with, but defeating them proved to be the most difficult of all. In 1879, Chief Victorio and some of his warriors bolted from their reservation and cut a bloody path across the Rio Grande and into Arizona. Their rampage lasted until Victorio's death in 1881. His son-in-law, Nana, half-blind and crippled by rheumatism, but still capable of riding seventy miles a day, then took up the hatchet and continued the war. Nana fought eight battles against the Americans and won them all, before coming into the San Carlos Reservation in eastern Arizona. In 1885, Nana escaped with Geronimo and raided until the final Apache surrender the following year. The most troublesome Indians were placed on a train and sent to Fort Marion, Florida, as prisoners of war.

With an end of hostilities and the virtual extermination of the buffalo, which quickly followed, the vast grasslands of eastern New Mexico were suddenly thrown open for settlement. Only some stray Apache bands in southwestern New Mexico had to be dealt with, but defeating them proved to be the most difficult of all. In 1879, Chief Victorio and some of his warriors bolted from their reservation and cut a bloody path across the Rio Grande and into Arizona. Their rampage lasted until Victorio's death in 1881. His son-in-law, Nana, half-blind and crippled by rheumatism, but still capable of riding seventy miles a day, then took up the hatchet and continued the war. Nana fought eight battles against the Americans and won them all, before coming into the San Carlos Reservation in eastern Arizona. In 1885, Nana escaped with Geronimo and raided until the final Apache surrender the following year. The most troublesome Indians were placed on a train and sent to Fort Marion, Florida, as prisoners of war.

Acknowledgments

A Campaign from Santa Fe to the Mississippi

Theodore Noel

Stagecoach Press, Houston, 1961

New Mexico, Revised Edition

Calvin & Susan Roberts

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2006

New Mexico; an Interpretive History

Marc Simmons

New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1977

"A Soldier's Experience in New Mexico"

John Ayres

New Mexico Historical Review 24, October 1949

Pueblo Land Grants: Confirmed by Congress (1854)

While the nomad tribes were suffering defeat and confinement on the reservations, the Pueblo people were preoccupied with adjusting to life under American rule. Mexico had recognized them as citizens and had provided special attorneys to protect their property rights, but it appeared that the United States was unprepared to grant them these privileges and unwilling to make any legal distinction between Pueblos and the warlike nomads.

New Mexico's first Indian agent, James S. Calhoun, recognized the special problem as early as 1849. He informed Washington that the industrious Pueblos were model subjects and urged that they be extended voting rights and that their land grants, given by Spain, be protected. The last point was particularly important, because the Indians, holding some of the best-irrigated agricultural lands in the territory, were constantly bothered by trespassers and squatters. The U.S. Surveyor General did confirm original Pueblo grants after 1854, a ruling reaffirmed by Congress. But the duty of the federal government to intervene actively to protect Pueblo Indian lands from encroachment, the policy Spain had pursued, would not be recognized until 1913.

By and large, the Pueblos had to wait until the opening decades of the twentieth century before much notice was taken of them, but Abraham Lincoln offered one small gesture acknowledging their existence in 1863. As early as 1620, the Spanish government had presented silver-tipped canes, or staffs of justice, to the Pueblo Indian governors as a symbol of authority. The canes, carefully preserved, continued to be passed down from one official to another long after Spain had given up her hold on New Mexico. President Lincoln, hearing of the custom and wishing to honor the Pueblos for remaining neutral during the Civil War, prepared a new set of canes, each with a silver crown upon which was engraved the name of the pueblo, the date of 1863, and the signature A. Lincoln. These gifts were honored alongside the original Spanish staffs; even today, when the Pueblos inaugurate their governors each January 1, both canes are ceremoniously conveyed to the new officials.

Period of Growth and Development (1868 – 1880)

Throughout the Southwest, railroad promotion was in the air, and in New Mexico's rugged mountain ranges, prospectors with picks and hammers were beginning to uncover deposits of gold, silver, copper, and other minerals. For those men for whom railroading or mining held little attraction, the territory's plains and basins, from which the last hostile Indians were then being cleared, provided abundant room for staking out a princely sheep or cattle ranch.

The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe, besting it rival, the Denver and Rio Grande Western, for possession of Raton Pass, became the first to lay rails into New Mexico from the east. Following the heavy ruts of the Santa Fe Trail, it reached Las Vegas early in 1879. Continuing westward, the railroad bypassed Santa Fe and curved down the Rio Grande valley to Albuquerque. It reached south to a division point at Rincon. There, one branch was extended to El Paso, while the other ran to Deming, where, in 1881, it forged a transcontinental link with the Southern Pacific that was building eastward from California.

New Mexico at that time already possessed one of the oldest mining industries in America. In the Cerrillos Hills south of Santa Fe, Pueblo Indians for centuries had worked open-pit turquoise mines, removing some one hundred thousand tons of waste rock, with nothing more than muscle and primitive tools. The Spanish showed little interest in turquoise, but they did extract lead, coal, and considerable copper from the Santa Rita del Cobre Mines near Silver City. During the Mexican period, a short-lived gold rush drew fortune seekers to the Ortiz Mountains south of the Galisteo Basin.

New Mexico at that time already possessed one of the oldest mining industries in America. In the Cerrillos Hills south of Santa Fe, Pueblo Indians for centuries had worked open-pit turquoise mines, removing some one hundred thousand tons of waste rock, with nothing more than muscle and primitive tools. The Spanish showed little interest in turquoise, but they did extract lead, coal, and considerable copper from the Santa Rita del Cobre Mines near Silver City. During the Mexican period, a short-lived gold rush drew fortune seekers to the Ortiz Mountains south of the Galisteo Basin.

The crescendo of New Mexico's mining boom had passed by the early 1890s, but while it was in its noisy prime, it pumped much-needed wealth into the territorial economy. The wealth proved real enough, just not large enough to fulfill the extravagant dreams of those who pegged their hopes on a never-ending supply of precious metal. In the wake of the bust, the high country was littered with ghost towns and abandoned tunnels whose only occupants were swarms of shrieking bats.

As early as 1865, beef contractors for the Bosque Redondo Reservation were encouraging stockmen to drive cattle from the plains of west Texas up the valley of the Pecos River to feed the captive Navajo. Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, among the early participants in that activity, took their first herd of longhorns to New Mexico in the summer of 1866. Even though others had blazed their route up the Pecos, it soon became known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail, and when in succeeding years it was extended to Colorado and beyond, it came to rank with the Sedalia and the Chisholm trails as one of the great cattle thoroughfares of the American West.

Acknowledgments

Early Railroad Days in New Mexico, 1880

Henry Allen Tice

Stagecoach Press, Santa Fe, 1965

Las Vegas Gazette

November 25, 1875

Period of Lawlessness (1875 – 1916)

With improved communication and promotion of New Mexico's bountiful resources, more and more people from the far corners of the nation began arriving to stake out and claim a piece of the territory for their own. Among them, inevitably, came the lawless preying on the settlers in the mining camps, railroad towns, and cattle ranches. From the end of the Civil War to the end of the century, most men wore a gun belted to the waist, and dance hall keepers installed signs that read, "Don't shoot the musicians, they are doing the best they can."

The Colfax County War (1875 – 1878), one of the more prominent disturbances, pitted claimants of the nearly two-million-acre Maxwell Land Grant against squatters who had settled on what they regarded as public domain.

The bloody disorders in southern New Mexico that came to be known as the Lincoln County War (1878 – 1881) attracted even greater attention. There, within the 27,000 square miles embracing the largest county in the United States, rival factions composed of merchants and cattlemen fell to feuding. Complete lawlessness soon reigned, as rustlers and gunfighters arrived from all parts of the Southwest to take advantage of the turmoil. Among them was the young William Bonney, alias Billy the Kid. By the summer of 1881 the Lincoln County War was burning itself out. The last phase came to an end when Sheriff Pat Garrett shot down Billy the Kid at Fort Sumner.

The bloody disorders in southern New Mexico that came to be known as the Lincoln County War (1878 – 1881) attracted even greater attention. There, within the 27,000 square miles embracing the largest county in the United States, rival factions composed of merchants and cattlemen fell to feuding. Complete lawlessness soon reigned, as rustlers and gunfighters arrived from all parts of the Southwest to take advantage of the turmoil. Among them was the young William Bonney, alias Billy the Kid. By the summer of 1881 the Lincoln County War was burning itself out. The last phase came to an end when Sheriff Pat Garrett shot down Billy the Kid at Fort Sumner.

Acknowledgments

History and Government of New Mexico

John H. Vaughan

Privately printed, Las Cruces, 1931

The Dream of Statehood is Realized

Even in the midst of civil strife and political storms, New Mexico was edging toward a social and cultural transformation. But the changes beginning to take place and the society that was emerging showed only marginal similarities with the development then going on in other areas of American's West. New Mexico, despite immigration from the eastern United States, steady economic growth, and a gradual increase in educational institutions, all of which drew the territory closer to the mainstream of national life, still remained a land apart.

Much of the reason resided in the continuing dominance of the Hispanic population. Throughout territorial days, and indeed until the 1940s, descendants of the colonial Spanish constituted a majority of New Mexico's people. In the other borderland provinces acquired from Mexico in 1848, Texas, Arizona, and California, the original inhabitants, by contrast, had quickly been swamped by incoming Anglo-Americans and their Hispanic culture was either buried or relegated to small, isolated islands within the new English-speaking society.

For a long time in the nineteenth century, New Mexicans were allowed to move along at an unhurried pace, and to follow their Old World customs without interference because other Americans were hardly aware of their existence. Gradually, of course, by a process of accretion, American ways made inroads. Yet the framework of Hispanic culture was kept intact and continued to serve as the principal point of reference by which the people viewed their past and measured the future.

For a long time in the nineteenth century, New Mexicans were allowed to move along at an unhurried pace, and to follow their Old World customs without interference because other Americans were hardly aware of their existence. Gradually, of course, by a process of accretion, American ways made inroads. Yet the framework of Hispanic culture was kept intact and continued to serve as the principal point of reference by which the people viewed their past and measured the future.

Some Americans remained skeptical that New Mexicans were loyal and worthy American citizens. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, President William McKinley sent a telegram to Governor Miguel A. Otero, Jr., at Santa Fe, asking him to assist in recruiting stalwart young men who were good shots and good riders. Otero, the first Hispanic governor of the territory, knew he was on the spot. "Many newspapers in the East," he later told an interviewer, "were dubious about our loyalty we having such a large Mexican population." Hoping to lay suspicions to rest, Governor Otero issued a call to every town and ranch in the territory for volunteers and offered his own services, if needed. The response from both Hispanics and Anglos was so generous that afterward Theodore Roosevelt would claim that half the officers and men of his famous Rough Riders Regiment came from New Mexico.

In 1898 Congress passed the Fergusson Act providing for the foundation of a public school system in the territory.

In 1910 Congress passed the Enabling Act, signed by President William Howard Taft. It provided for the calling of a constitutional convention in New Mexico. The conservative document that body drafted was ratified by voters early the following year, and on January 6, 1912, New Mexico became the forty-seventh state in the Union.

Acknowledgments

"New Mexico's Fight for Statehood, 1895 – 1912"

Marion Dargan

New Mexico Historical Review 14 (January 1939): 11

New Mexico's Quest for Statehood, 1846 – 1912

Robert W. Larson

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1968

Statehood: Unresolved Questions of Spanish Land Grants and New Settlers

With the growth of New Mexico's population, land values rose and attracted investment capital into the territory. Many newcomers found that millions of acres of the best land for farming, ranching, and logging lay beyond their grasp. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo had promised to protect the ownership rights of the heirs of land grants. The difficulty of fulfilling that promise became apparent only later, as differences in Spanish and Anglo concepts of law and land tenure began to raise complex legal questions. The most flammable of these involved the old community land grants, which had been made by Spain and Mexico. Originally, under terms of such grants, settlers had received individual title to the small amount of farmland available along the irrigation ditches, while the remainder of the grant was held in common for purposes of grazing and wood gathering. The boundaries of the community holdings, in the absence of surveyors, were inexactly delineated, using such natural landmarks as large rocks, prominent trees, springs and arroyos. Within a short time after establishment of the American legal system, complications arising from these Hispanic practices produced a tangled web of claims and counterclaims and opened the way for speculators to obtain, often through deceit and fraud, a controlling interest in some of the most valuable grants.

Congress took a sidelong look at the problem and handed it to the Office of the Surveyor-General, which was created in 1854 for the specific purpose of adjudicating Spanish and Mexican land titles. At the time, New Mexico had more than one thousand claims awaiting settlement, some of them dealing with the community grants and others with large private grants that had once been allotted to individual Spanish families. The first surveys showed that many of the old boundaries could no longer be accurately defined and that often the grants had overlapping claims. Legitimate descendants of grantees seldom possessed their original papers, and some of those who did, through fear or distrust of the alien legal procedures now imposed upon them, failed to bring the documents forward to receive new patents for their lands.

In the forefront of those who profited from such a situation were the lawyers – the class of men who Father Martinez had predicted in the 1850s would supplant priests as the real power in New Mexico. For clearing titles, they exacted huge fees. These fees were usually paid in land from that held in common, so that, within time, as seemingly endless litigation over titles continued, sharp-eyed American lawyers and their associates acquired possession of prodigious sections of the Spanish grants. One Santa Fe attorney, for example, was reported by a local newspaper in 1894 to have an interest in seventy-five grants and to own outright nearly two million acres.

One of New Mexico's leading land grant authorities commented, "Only a few claims were confirmed and patented under the Surveyor-General, and by the 1880s speculation in the grants had reached the point of national scandal." As a result, a Court of Private Land Claims was established in 1891 in a bid to settle the many controversies by judicial means. Although that body succeeded in adjudicating all claims by 1903, it sowed the seeds of future discord by accepting and continuing a precedent regarding community grants that had been laid down by earlier courts.

Unfamiliar with Spanish law protecting and preserving village commons, American judges had ruled that the ancient common lands could be partitioned and divided among the numerous grant-claimants. That meant that vast areas of upland pastures and mountain woods, of which villagers had made free use for generations, were now allotted to individuals who could put them up for sale if they chose. Not surprisingly, surrounding lands soon slipped from the grasp of community members and passed to the control of outsiders, often cattlemen from Texas, or into the public domain, where much of it was placed under the National Forest Service. A similar pattern of land loss was experienced by a number of American Indian tribes in the twentieth century, when by Congressional Act their reservations were broken up and the land granted in severalty, thereby destroying the common-property base of community existence.

Acknowledgments

The Far Southwest, 1846-1912

Howard Roberts Lamar

Yale University Press, New Haven, 1966

A Brief History of New Mexico

Myra Ellen Jenkins and Albert H. Schroeder

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1974

The Bursum Bill

Politics divided many New Mexicans during the 1920s, however New Mexico's Pueblo Indians united in a common cause, for the first time since the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, against government actions that they perceived as threatening their land and way of life. Although the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo had promised that New Mexico's Native Americans would retain their land and the Office of the Surveyor-General had confirmed Pueblo land titles, the U.S. Government had generally ignored the Pueblo peoples. In 1876, however, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision that eventually threatened Pueblo lands. In reaching the conclusion that the Pueblo peoples were more advanced culturally than other Indian groups, the court declared that they were not dependents of the federal government and therefore had the authority to handle their own lands as they saw fit. The result of this decision was that individual Indians sold 30% or more of Pueblo lands to non-Indians during ensuing decades. Then, in 1913, the high court again spoke on the issue of Pueblo lands by reversing its earlier decision and declaring that the Pueblo peoples were indeed dependents of the federal government and that non-Indian claims to Pueblo lands were consequently illegal.

This new ruling created the immediate problem of what to do about the three thousand non-Indians who owned Pueblo land, especially since some of those families had lived on this land for two or more generations. In 1921 Albert Fall, as Secretary of the Interior, sought a solution to the problem by asking his successor in the U.S. Senate, Holm O. Bursum, to draft an Indian land bill. Bursum's bill gave non-Indians ownership of Pueblo lands they had acquired before 1920, and it permitted the state courts, long unsympathetic to Indians, to settle all future disputes over Pueblo land titles. If it had passed, this bill would have spelled disaster for the Pueblo peoples because it would have meant the permanent loss of some of their best, irrigated land.

Support for the Pueblo cause in response to the Bursum Bill came from a group of artists and writers who had settled in Taos. John Collier, the young poet invited to New Mexico by Mable Dodge Luhan, took it upon himself to travel with Tony Luhan from pueblo to pueblo to let the Indians leaders know what was being proposed for them. When the Indians learned of the contents of the bill, they were stunned. No federal or state leader had even informed them that an Indian land bill was being considered. As Collier rallied support for the Pueblo peoples among his artist and writer friends' throughout the country, the Indians themselves began to unite. Pueblo leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., to appear before Congress. Widespread support for the Pueblo cause drew national attention, and the immediate result was the defeat of the Bursum Bill.

The attention aroused by the furor over the Bursum Bill also brought improvements in federal Indian policy. In 1924 Congress passed the Pueblo Lands Act, which recognized once and for all the land rights of the Pueblo peoples and provided compensation for the property, which under the law, non-Indians were to give up to the Pueblos. In the same year, Congress passed a second act that addressed the rights of Indians; this law provided American citizenship for Indians born in the United States. Arizona and New Mexico, however, did not allow Indians to vote in national and state elections until 1948, when a federal court ruled that all states had to give Indian peoples the right to vote.

Acknowledgments

New Mexico, Revised Edition

Calvin & Susan Roberts

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2006

John Prather's Rebellion: A Fight for Individual Rights (1957)

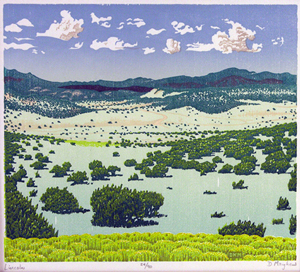

John Prather's name is not one generally found in formal history books, but his story is both compelling and inspiring.In 1883, John Prather and his brother Owen came to New Mexico on horseback, from Texas. As part of the last wave of the western movement, they were seeking free land at a time when most of the prime land had already been claimed. The Prathers were stockmen, and as they rode, they looked with admiration upon the grassy plains of southeastern New Mexico. Having no desire to compete with either the established ranchers or the encroaching sodbusters, they kept moving. Beyond the Pecos, they followed a pass through a ridge of mountains and emerged upon the western slope to see, dipping before them, the shimmering expanse of the Tularosa Basin and the distant dark ridge of the San Andres Range.

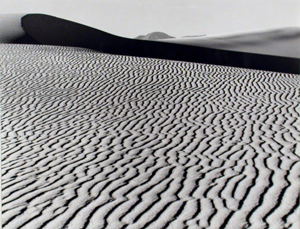

What they had entered, after their trip over the plains and through the cool mountain forest, was a different world – a kingdom whose pebbly soil could support only a thin mantle of grass and scattered clumps of yucca and greasewood. Gypsum flats, and lava beds covered great sections of the land, and summer's blazing light and dry heat shriveled every living thing. The White Sands, a lake of shifting, glittering gypsum dunes, reached fifty miles north and south down the center of the basin and served as a playground for little whirlwinds, called dust devils, whose antics could be followed by anyone with a perch in the mountains fifty miles away.

What they had entered, after their trip over the plains and through the cool mountain forest, was a different world – a kingdom whose pebbly soil could support only a thin mantle of grass and scattered clumps of yucca and greasewood. Gypsum flats, and lava beds covered great sections of the land, and summer's blazing light and dry heat shriveled every living thing. The White Sands, a lake of shifting, glittering gypsum dunes, reached fifty miles north and south down the center of the basin and served as a playground for little whirlwinds, called dust devils, whose antics could be followed by anyone with a perch in the mountains fifty miles away.

Such hard, inhospitable country – much of it then in Lincoln County – attracted a certain breed of men. Restless and roistering men were drawn to it, especially those who felt uncomfortable in crowds, shunned society's constraints, and were at ease with solitude. In those early days, almost everyone else was prepared to leave the Tularosa kingdom to the Apaches and the jackrabbits; and they joked, after seeing natives grubbing roots for fuel and bringing water on burros from the mountains, that this was the only place on the continent where men, reversing the usual order of things, dug for firewood and climbed for water.

But is was here that John Prather, after some shifting about, settled on a spot with fair grass below the Sacramento Mountains and went to raising cattle. Owen, nearby, began developing a sheep ranch. Decades crept by, wars and depression bedeviled the outside world, and all the while under the flaming New Mexican sun, John Prather worked his stock and continued to improve his property of some four thousand deeded acres and an additional twenty thousand acres leased from the government.

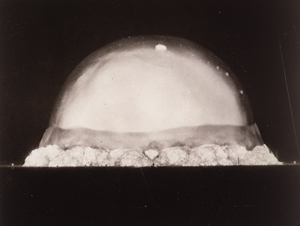

Then World War II changed all that for the Tularosa country and for all the off-the-path pockets in New Mexico that had kept one foot planted in the nineteenth century. It had its beginning on the pine-clad summit of the Pajarito Plateau west of Santa Fe. Upon the plateau in 1943, the U.S. government sealed off a tract of land and built the secret city of Los Alamos around an atomic energy laboratory. Scientists living with their families in almost complete seclusion soon produced the first atomic bomb and tested it on July 16, 1945, at the Trinity Site in the desolate White Sands of southern New Mexico.

The explosion of the atomic bomb at the White Sands Proving Ground (now the White Sands Missile Range) was felt over much of New Mexico in that summer of 1945. But it was what followed that proved more disturbing to the residents of the Tularosa Basin. The military was in need of land, a great deal of it, for the testing of rockets and the training of their crews, a program deemed crucial for national defense. To expand the range, hundreds of thousands of acres were ordered withdrawn from the public domain and from private ownership, which meant condemnation proceedings were instituted against surrounding ranchers. Many of these people waged fierce court battles and appeared at congressional hearings in a bid to keep their land, but one by one, over succeeding years, they lost out and were displaced.

The explosion of the atomic bomb at the White Sands Proving Ground (now the White Sands Missile Range) was felt over much of New Mexico in that summer of 1945. But it was what followed that proved more disturbing to the residents of the Tularosa Basin. The military was in need of land, a great deal of it, for the testing of rockets and the training of their crews, a program deemed crucial for national defense. To expand the range, hundreds of thousands of acres were ordered withdrawn from the public domain and from private ownership, which meant condemnation proceedings were instituted against surrounding ranchers. Many of these people waged fierce court battles and appeared at congressional hearings in a bid to keep their land, but one by one, over succeeding years, they lost out and were displaced.

Then, in 1955, the government, as it crept eastward toward the Sacramento Mountains swallowing up chunks of ground, ran straight into eighty-two-year-old John Prather. His land, which he had held and worked for fifty years, was not for sale, Prather announced. Anyone who tried to put him off might get hurt. In the U.S. District Court at Albuquerque, a condemnation suit resulted in a ninety-day eviction notice for John Prather and his neighbors. The old man's response to that was to issue a public statement: "I'm going to die at home."

By now, August 1957, the episode was spread across the front pages of the nation's leading dailies, and reporters were pouring into El Paso, where they looked for transportation northward to the Tularosa Basin. At the ranch, Prather's kin had arrived, twenty-five in all, and they joined in fortifying the main house in preparation for a siege. As jeeps brought in army officers and newsmen over a dusty, washboard road, it appeared the basin's first battle since the days of the Apache wars was about to be fought.

Officials, however, had had enough. Public opinion was clearly swinging to the side of the courageous old rancher, and since he could not be moved, short of force, a directive from Washington ordered military personnel to withdraw from the Prather Ranch. The army then went back to court and obtained a new writ exempting the ranch house and fifteen surrounding acres from confiscation; the remainder of the land was forthwith annexed to the military reservation. If John Prather raised no further fuss, he would be left alone.

That ended the matter. Prather had lost his ranch, but he had also won a victory of sorts. Standing firm, he had forced the U.S. government to compromise and in so doing had chiseled himself a niche in the history of southern New Mexico. As one writer later explained it, John Prather reacted as his forebears had reacted against invasion of their independence and property rights. His was the code and psychology of the eighties, and he was the last of his kind.

Acknowledgments

New Mexico An Interpretive History

Marc Simmons

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1977

Tularosa, Last of the Frontier West

C.L. Sonnichsen

The Devin-Adair Co., Old Greenwich, Conn., 1972

What Steps Did Californians Take to Apply for Statehood

Source: https://online.nmartmuseum.org/nmhistory/people-places-and-politics/statehood/history-statehood.html

0 Response to "What Steps Did Californians Take to Apply for Statehood"

Post a Comment